Introduction

Stimuli are defined as any event, object, or change to the environment, often serving as the antecedent to a behavior. Stimuli can be a person, a place, or the materials presented.

In ABA therapy, it is important to teach in a way that aids the learner in applying learned skills across different situations or various stimuli based on past knowledge or experience. Stimulus generalization is the ability to take one example and apply what is known to other similar stimuli. When stimulus generalization occurs, the learner can form concepts in the natural setting without being specifically taught each skill through discrete trial training.

Think of stimulus generalization as being able to read the same sentence in different fonts and different handwriting. The letters are the same and are recognized as such, but the way the letters look is varied.

The process of stimulus generalization can look like a child seeing an animal for the first time. The child will use past knowledge to form new thoughts about the new animal. They may think “it looks like a horse, but it has stripes.”

For this thought to form, the child must know what a horse is, and then they identify the characteristics that make the new animal like a horse.

The child was also able to identify what made the new animal NOT look like the horses that they had previously seen. The child must also know what stripes are and be able to generalize that different things can have stripes, including animals.

The child might go back to an adult and say, “I saw an animal that looked like a horse with stripes,” and the adult then labels the animal for the child.

“Oh, that’s smart, that animal is a zebra!”

The child now knows the name of the new animal and will add zebra to their language and memory.

Children start to generalize in rudimentary ways around 18 months of age. Classifying develops at around 3–4 years. Stimulus generalization isn't a single-step skill, but a gradual learning process, starting with perceptual patterns and moving to abstract events and social understanding.

Why Stimulus Generalization Matters

In behavior analysis, we should start programming for generalization as soon as possible. This is especially important when working with children with learning differences. Some learners are very skilled at memorization; this can be counterproductive for stimulus generalization, making it harder to teach and maintain more complex skills over time.

If a child has any tendency for rigidity or sameness, they may not be able to generalize and continue learning outside of very specific settings, people, and materials.

A Brief Scenario: Generalization in Everyday Life

Child learns “hello” in therapy → greets in real life

At home, a baby engages in peek-a-boo with a parent, and the parent and child both smile and laugh during the game.

The child then covers their face playfully to engage in peek-a-boo when they make eye contact with a novel adult at the grocery store.

Playing peek-a-boo has become a generalized response across adults who smile at the baby.

Programming for Stimulus Generalization

The first steps that a behavior analyst can take to program for stimulus generalization are to use real examples, use multiple exemplars, and teach prerequisite skills across the verbal operants.

In ideal scenarios, you would also program to have the learner perform skills across various adults, peers, and settings.

If you were teaching a child to label a person running, the best way to do so is to have an actual person run as opposed to showing them a picture of someone running. The next best stimuli would be a video of someone running.

A good data collection platform, such as Theralytics, can track this target across the different stimuli presentations. Accurately tracking this target will help the behavior analyst and RBT stay organized and focused on client progress.

To promote stimulus generalization, the behavior analyst would ensure that many different examples of a person running are used in teaching. This is known as multiple exemplar training, a technique that aims to teach the learner to respond to a varied group of stimuli instead of one specific trained stimulus.

The behavior analyst should consider the prerequisite skills required for performing the target of labeling a person running. The learner’s program should be tailored to teach across the operants.

Can the child perform the skill of running when asked?

Can they label themselves running?

Can the child label a boy or a girl?

If the target response is “boy running” or “girl running.”

If the target response to the question “what do you see?” is to use the person’s name (“Avery running”), does the learner know that person’s name?

The most common pitfalls are attempting to teach a skill that the child has not yet mastered the prerequisites to perform.

When you think about how math skills are taught, you cannot move to the next concept without mastery of the prerequisite. You master addition before subtraction and before moving to multiplication.

It is also counterintuitive to prompt a response; allowing the child to memorize the answer, and then they can only perform the skill under one set of specific conditions. This isn’t mastery of the concept; this is rote memorization.

As a behavior analyst, these are factors to be considered when programming and supervising RBTs. Being able to learn a concept and apply skills flexibly is a strong indicator that a child can generalize and will likely be more successful in a less restrictive environment.

Failure to generalize is a barrier identified in the VB-MAPP Barriers Assessment, and generalization of skills across time, settings, behaviors, materials, and people is scored in the Transition Assessment.

What Is Stimulus Generalization

Definition (Classical & Operant)

Stimulus generalization can be described as responding to similar stimuli in the same manner as the original stimuli.

If a child has a dog at home named Max, and then they call all other dogs Max. This example describes classical stimulus generalization, which relies on similar stimuli.

Operant stimulus generalization focuses on applying a learned response in a similar context or setting and relies on similar consequences or outcomes.

Both types of stimulus generalization are important for learning and development and should be considered when programming in ABA therapy.

Behavioral / ABA Framing

When thinking about language and how stimulus generalization skills are acquired, it involves asking questions and giving the learner the tools to form their own hypothesis.

Teaching across the operants and teaching the inverse are useful techniques. Teaching characteristics, categories, and negation skills should also be considered.

If you have trained a learner on the characteristics of what makes something an animal and they have mastered common animals, such as fox, bear, horse, cow, dog, and pig, you can then add in a bit of novelty by also presenting a lion or a deer.

The lion and deer share some of the characteristics of the trained animals listed. If stimulus generalization has occurred, the learner will categorize the lion and deer as animals.

Even if the learner doesn’t know the names of these animals yet, you could start by having them match non-identical animals or sort people and animals into groups.

The lion and deer could be presented as LRFFC targets, “touch the one that is an animal.”

Presenting tasks in various ways using varied stimuli is all useful when the goal is stimulus generalization.

Relationship to Stimulus Control

How Stimuli Come to Control Behavior

How do we get a response that is occurring under one set of conditions to happen under a different set of conditions? The answer is stimulus control transfer, which is a skill assessed during RBT competency.

The best way to think about this is to recall the unconditioned responses of a newborn baby. Newborns need milk, warmth, physical touch for comfort, sleep, oxygen, and relief from pain or distress (like having a soiled diaper or being cold), all crucial for survival and well-being, and for establishing foundational learning. The only behavior that they are equipped with to communicate their needs is crying. Crying is automatic if one of their innate needs is not met.

Fast forward 6–8 months, and a lot of new behaviors are paired with the baby’s needs being met with reinforcement. Crying when hungry becomes crying and reaching for their bottle, then the crying is dropped, and they now only need to reach for their bottle to be given milk.

A few months pass, and the baby is now saying “ba-ba” and reaching, then they drop the reaching, and they only say “ba-ba” to be given milk.

How did this learning happen? Each new behavior was reinforced, and other pairing techniques naturally occurred throughout the process as well. The baby’s caregiver likely labeled “ba-ba” as they made the bottle, the baby imitated this sound and connected that “ba-ba” leads to milk (reinforcement). The sight of a bottle now elicits the word “ba-ba.” These associations were strengthened over time through conditioning.

This learning process can be sped up in ABA therapy by prompting the new response and conducting a transfer trial using one response to teach another, and providing reinforcement immediately following.

If the learner can echo words, and we want them to mand for the swing on the playground, we will model by saying the word “swing,” the child echoes “swing,” and we push them on the swing.

Now the stimulus transfer would entail the same steps with an additional and very important step. We model by saying the word “swing,” and the child echoes “swing.” We say, “What do you want?” and the child says, “swing.” We push them on the swing.

So we are going from an echoed response of “swing” contacting reinforcement to the question “what do you want?” controlling the response “swing” and contacting reinforcement (being pushed on the swing).

Examples of Stimulus Generalization

Classical / Everyday Examples

(Little Albert’s fear generalization)

When classical stimulus generalization occurs, similar stimuli evoke the same response. If a baby is startled by the loud noise of a metal bowl being dropped on the floor and starts to cry, another loud noise will cause the baby to cry.

We can think of classical conditioning as utilizing unconditioned responses (reflexes), while operant generalization is based on learning history and voluntary responses.

Operant / ABA Context

(Greeting across people, zipping different jackets)

When operant stimulus generalization occurs, similar situations will be met with the same response. Voluntary behavior impacts the consequence. If I do this, the outcome is likely to be like the last time this situation happened.

An example would be using markers or colored pencils to draw a picture, because the result is similar in both situations.

Classical and operant stimulus generalization go hand in hand. If you have been brand loyal to Oreo, you may try the store-brand cookies that are in similar packaging (classical stimulus generalization).

Let’s say you buy the store brand several times and they taste like Oreo’s (reinforcement has occurred in the presence of similar cookies). Now you go to a different grocery store, and they also have their version of the cookies. You are likely to buy this novel store brand because the behavior of buying store-brand cookies has been reinforced in similar situations (operant stimulus generalization).

Why Stimulus Generalization Is Important

Stimulus generalization is important for several reasons. One reason is that it makes skills transferable to the real world and creates better long-term outcomes.

When a learner can generalize a skill, this promotes independence and less reliance on the prompting of others. Programming becomes more efficient because novel stimuli and novel scenarios can be used instead of specifically adding every stimulus to be trained.

The learner begins to respond more naturally, which decreases rigidity and rote memorization.

When stimulus generalization is ignored, the learner is often responding by memorizing, becomes very reliant on prompting, and is less likely to succeed in less restrictive environments.

It’s especially important that ABA programming considers how to teach with stimulus generalization in mind from the start. Skills should not be considered mastered if they can only be performed under one set of conditions.

When skills are prompt-dependent or stuck in one scenario, we run into the trap of teaching to the assessment instead of promoting transferable skills.

Stimulus Generalization vs. Stimulus Discrimination

Stimulus Generalization

Responding in the same manner to varied stimuli

Stimulus Discrimination

Differentiating between various stimuli and adjusting the response

Thinking of the example from earlier in this article, the child saw a picture of a zebra and recognized it as a horse with stripes. This shows that the characteristics of a horse are generalized, but the child also used stimulus discrimination, recognizing that it could not be a horse because of the stripes.

One of the first things we see when language develops is overgeneralization. Think of a toddler who calls every man they encounter “daddy.” Pretty quickly, discrimination develops, and the toddler knows their own father’s characteristics compared to the characteristics of other novel men.

Discrimination develops because reinforcement only follows the response that occurs under the correct stimulus.

Recalling the earlier topic of teaching the category of animals to a child, as discrimination develops, the child has more information and experiences to use that narrows the category even further. They could learn to discriminate between farm animals and jungle animals, reptiles compared to mammals, and so on.

As learning expands through contacting reinforcing variables, the child gains information to continue building their knowledge base. This allows them to know when to generalize and when to use discrimination skills.

Memory Aids, Rules, and Discrimination

One way we teach people to recall learned information is by using memory aids and mental rules. We teach through songs, acronyms, and connecting the information to previous information or experiences.

In ABA therapy, we need to consider using memory aids and mental rules as an effective therapeutic tool. The new information becomes more salient when the child can have hands-on experience or when they can tie the concept to something visual.

If we can provide a rule to apply to a situation, this also helps with memory and information recall.

For example, when teaching intraverbals (a verbal response to verbal stimuli), a more effective prompt is to have the learner tact a picture rather than using an echoic prompt. You’re helping tie the answer to an image, creating a mental snapshot that they can later recall and use to answer various types of demands.

There are several cases in which it is better to discriminate instead of overly generalizing. When you send your partner to the store and say, “Buy a box of cereal,” versus “Buy a box of Cheerios.”

The more a person can use discrimination to describe an object, an event, what they need, or what they want, the better. Discrimination is preferred when you need to increase accuracy and ensure the right response occurs under the right conditions.

Broad generalizations create communication breakdowns. If a child learns “more” as their first mand, they will typically overgeneralize this skill, and it doesn’t help them with making requests outside of very specific conditions.

If a child approaches a novel adult and says “more,” it’s likely this request will not be met with reinforcement. If a child approaches a novel adult and says “cookie,” the chances of getting a cookie increase.

In ABA therapy, behavior analysts prefer to teach mands using the names of the items versus general words like “more” to warrant stimulus discrimination for the speaker and the listener.

Response Generalization & Related Concepts

So far, we have focused on stimulus generalization. Now let’s shift to discussing varied responses to the same stimuli, also known as response generalization.

Response generalization occurs when you respond with a behavior that serves the same function or yields a similar outcome.

One of the responses we systematically vary in ABA programming is the mand carrier phrase. Teaching the child to say “Let’s play blocks,” “Can I have blocks,” “I want to play blocks,” and “Give me blocks” would all yield access to blocks.

Stimulus generalization looks at various stimuli yielding the same response, while response generalization examines various responses to the same stimuli.

When the varied responses are followed by reinforcement over time, this strengthens the response class. Timing is critically important to avoid rote memorization and teach flexible responding.

Generalization Gradient

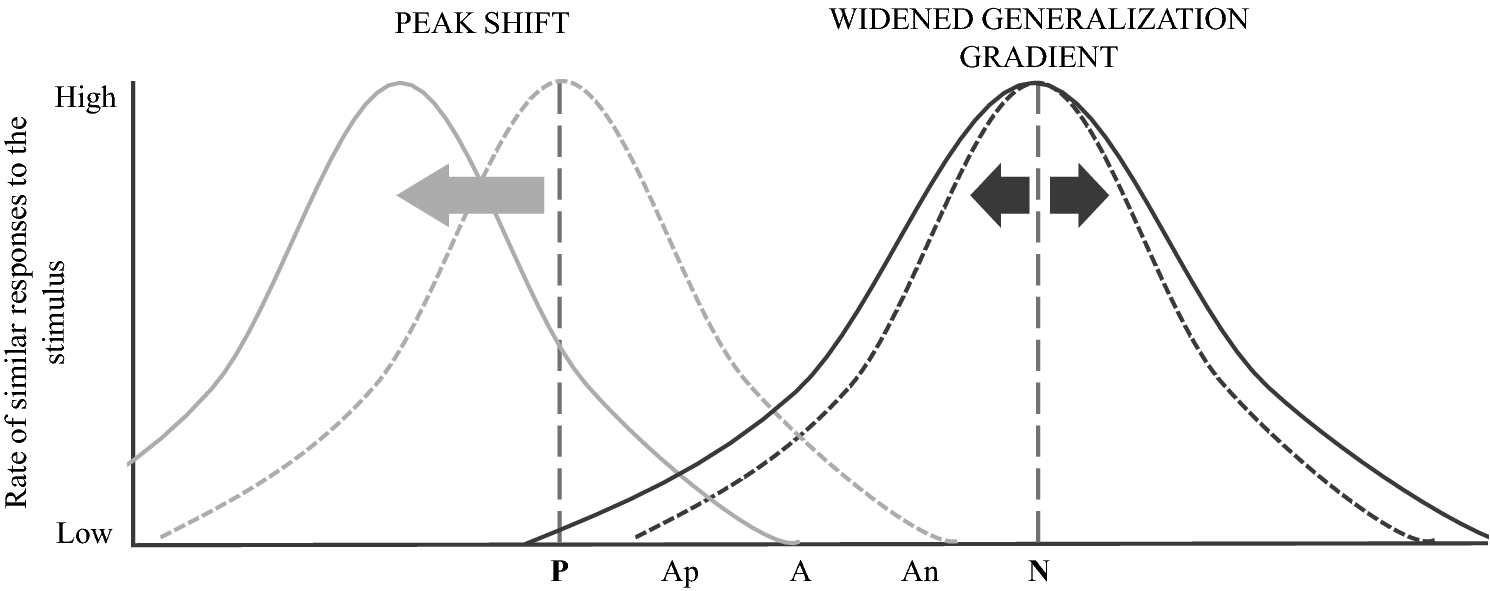

The generalization gradient refers to a graph depiction of how a learner responds to stimuli with more accuracy the closer those stimuli match the trained stimuli.

As expected, when a new stimulus is introduced, if it is very close to the original stimuli, the learner will respond correctly. When stimuli with less similarity are introduced, responding accuracy decreases.

The gradient looks like a bell, with the trained stimulus represented by the middle data point. The x-axis represents similarity, and the y-axis represents response strength.

Keeping the generalization gradient in mind while programming can help determine if there has been enough variation in stimuli introduced while maintaining accurate responding. If the graph does not show a bell curve, more training across varied stimuli is needed.

A Classic Experiment on Generalization & Discrimination

B.F. Skinner used stimulus generalization and discrimination in various studies. Rats were trained to press a lever to receive food pellets. Right away, the rats began pressing the lever at an increased rate to be given food pellets.

Skinner then introduced specific conditions, such as a light or sound, in which pressing the lever would be followed by receiving a food pellet. Through conditioning, the rats learned to discriminate when food was available.

When the stimulus was present, the rats pressed the lever. When it was not present, they did not press the lever.

Skinner’s experiments showed the impact of differential reinforcement during training and how it directly relates to stimulus generalization and discrimination. One response class is strengthened while previous responses are extinguished.

Strategies to Program and Promote Stimulus Generalization

ABA-Focused Approaches

Stokes & Baer (1977): Implicit Technology of Generalization

Stokes & Baer’s 1977 study documented a phenomenon of generalization occurring after training without specific programming, referred to as “Train and Hope.”

Sequential Modification involves systematically applying contingency modifications across non-generalized conditions, such as transferring clinic-based skills to home or school settings.

Introducing Natural Maintaining Contingencies supports generalization by ensuring behaviors contact reinforcement in natural environments. Peers can be a strong catalyst for maintaining behavior.

Training Sufficient Exemplars broadens the concept by using multiple similar examples during instruction.

Training Loosely reduces rote memorization by introducing varied stimuli early and often.

Indiscriminable Contingencies use intermittent reinforcement schedules, increasing resistance to extinction and promoting generalization.

Programming Common Stimuli involves using a salient stimulus across training and generalization settings, which is later faded.

Mediating Generalization involves explaining contingency changes so learners adjust their behavior accordingly.

Training to Generalize refers to reinforcing varied responses that serve the same function.

Step-by-Step: Designing a Generalization Plan

- Define the target behavior and mastery criteria

- Identify stimulus dimensions to vary (people, places, materials, instructions, time)

- Choose generalization strategies

- Decide on data collection and take data

- Fade support and prompting

- Monitor data

- Plan for maintenance and monitor drift

Measurement & Data: How to Know It Worked

When designing a program for generalization, it’s important to choose a data collection system that makes sense. Data may be tracked on both trained and novel stimuli.

Cold probes may be conducted, recording the first response of the day or session toward mastery.

Decision rules determine whether skills move forward or return to acquisition. Consider percent correct, consistency, and responding across instructors.

Checks for data accuracy may involve comparing data from multiple observers.

Using Theralytics, ABA teams can log generalization probe data and generate analytics over time. Clinicians can build custom probe modules and dashboards to track generalization across exemplars and time.

Conclusion & Next Steps

To build independence, ABA therapy targets stimulus generalization, enabling learners to take a skill learned with one stimulus and apply it to others.

This reduces reliance on repetitive training and allows for real-world application.

Strategies include varying stimuli, using multiple instructors, practicing in natural environments, fading prompts, and refining generalization technologies.

With electronic data collection platforms such as Theralytics, programming for generalization becomes more efficient, accurate, and data-driven, supporting better outcomes for learners.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: What is stimulus generalization in ABA?

Stimulus generalization is the ability to apply a learned skill to new but similar situations, people, or environments without direct teaching for each variation.

Q2: Why is stimulus generalization important in ABA therapy?

It ensures that skills learned in therapy transfer to everyday life, promoting independence and reducing reliance on prompts.

Q3: What is the difference between stimulus generalization and stimulus discrimination?

Generalization means responding the same way to similar stimuli, while discrimination means responding differently based on specific features.

Q4: How do behavior analysts promote stimulus generalization?

They use strategies such as training with multiple examples, varying stimuli and instructors, programming common cues, using natural reinforcement, and fading prompts systematically.

Q5: How is stimulus generalization measured?

By collecting data on responses to new stimuli, conducting cold probes, and tracking performance across different settings and people.

.avif)